Table of Contents

- Can you invest without risk with expected long-term passive income?

Introduction

While our thoughts and public narratives are occupied with the process of investing in and growing artificial intelligence, we may forget to appreciate the developing human potential and investing in it.

Nevertheless, my feminine approach to economics and business requires such a reminder, particularly in light of a new generation entering what is commonly referred to as the labor market.

This white paper serves as an invitation to discussion for the purpose of determining the most effective approaches to develop human and AI potentials in parallel, and it provides a summary of the topics that I examined and analyzed.

Can you invest without risk with expected long-term passive income?

Is there a way to spend that there is no risk?

Yes, there is. It’s an investment in people, and the earlier in life that investment is made, the better.

But it looks like we’re not serious about this business because it has parts that aren’t related to money that we don’t understand. We tend to stay away from things we don’t understand.

Why does that happen?

If we know that investing in people is the best way to make money, then why don’t government policies prioritize investing in children?

Why aren’t investments that help kids a top priority when it comes to laws and rules?

All of us know that health and knowledge are the best ways to ensure a better future. So why don’t our public investments match what we know?

How come the biggest chunks of public money aren’t spent on improving the health and safety of kids?

Why do parents still have to pay most of the costs of taking care of, educating, and protecting their kids?

How is it that young women have to choose between having children and careers?

I’ve been around long enough, learned enough, and experienced enough that it doesn’t bother me if someone says my ideas aren’t important because I’m not a mother.

My husband and I have decided not to have children because we were aware of the dimensions of poverty our children might have been exposed to.

I worked for years in an organization whose goal was to keep the promise that humanity made to children. I often repeated that children are not the future, but the present.

When is the best time to invest in human potential?

In my opinion, investments benefiting children and young people can not wait until tomorrow.

Because I’m old enough, I can say that there is no time to wait for political will, party deals, or popular priorities. I choose not to use geographical references because it doesn’t matter to me what country, community, or region is in question. In this day and age of migration, social injustice, and easy access to the internet, I strongly believe that everyone should live and work where there are more opportunities and chances.

The idea of a country fit for children is still just that—an idea. Even in well-developed economies and well-organized societies, there are children who don’t have the rights to safety, chances, education, or respect. There is enough public data on this topic, but the information is still insufficient. If there is no data, that might mean that something is not perceived as important, right?

Can we conclude that countries that don’t invest enough in the health and safety of their children may not be living out their patriotism?

What is actually considered an investment in favor of human potential?

It’s not just about giving cash to parents and providing social services; it’s also about the quality of schooling and health care. It’s also about fairness, respect, and chances. It has to do with kids feeling like they fit in society and are respected and heard. It’s not just the money we donate to children for medical care or grants; it’s also the time we spend thinking about their wellbeing.

Every child is a child, regardless of their abilities, where they live, or who their parents are.

It’s not just budget items; it’s also the awareness that their rights are unconditional.

In principle, we all agree on that.

So where do the problems arise, and why there are “invisible children” even in the wealthiest countries?

Because they are born inseparably linked to prejudices, limitations, and injustice, whether their parents divorce, whether their parents decide to live where it’s better for them, making them a minority, or whether they are born with developmental disabilities or surrounded by poverty.

Why should we care about other people’s children?

Why should we care about other people’s children, someone asks. Because of the question in the title.

If we don’t understand fairness and social responsibility, can we at least consider economic logic?

So, how do we invest in favor of children?

As a wise woman once said, “Let’s look into the eyes of a child who is not ours and ask ourselves how to increase their chances in life, not for one day by buying cheap gifts, but by acknowledging the simple fact that this child is not the future, but the present.”

A child is the present rather than the future

A few years ago, I was fascinated by the documentary series “The Beginning of Life” on Netflix.

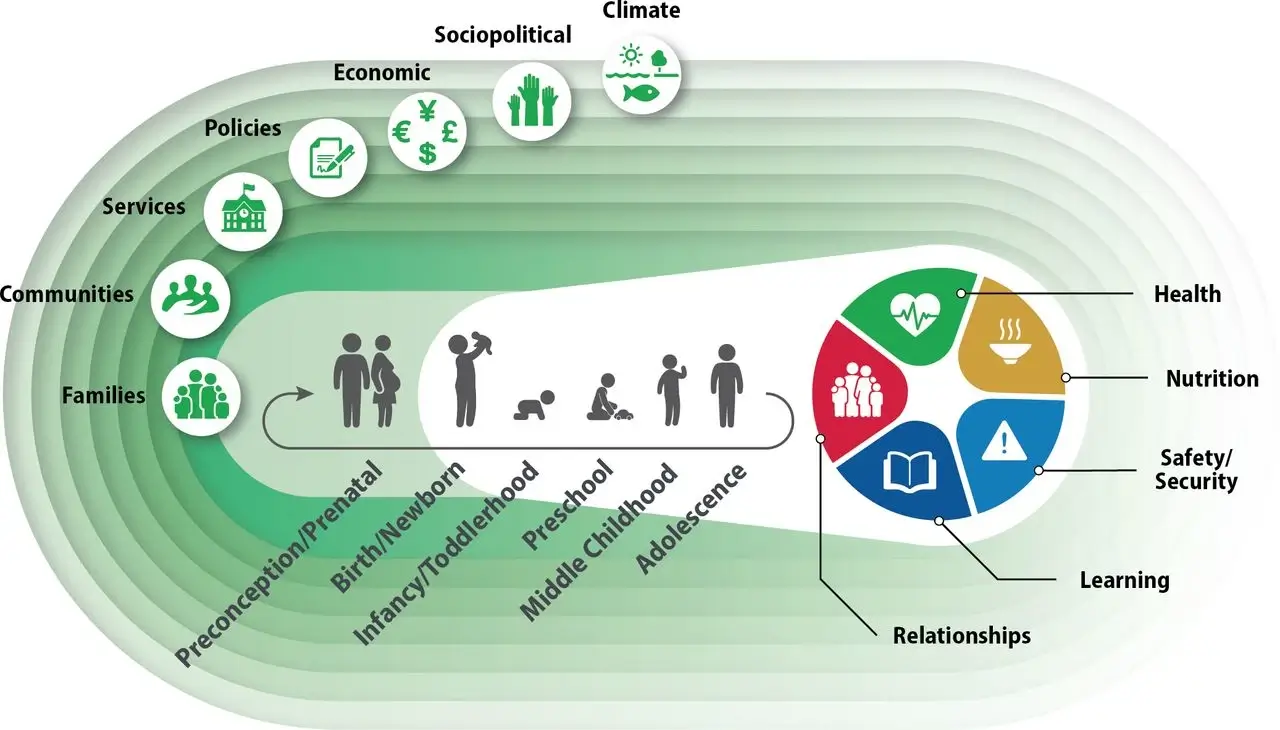

Although it didn’t achieve as many views as popular titles, even the trailer promised, “If we change the beginning, we change the whole story.” Scientists have been collecting evidence from the natural and social sciences for decades, showing that timely investment—meaning in the early years of life—is crucial for success in life.

A newborn’s brain already contains almost all the neurons it will ever develop.

About 80% of the brain develops in the first three years of life, and by the age of five, 90% of the brain is formed, according to science.

Although abilities continue to develop throughout life, research indicates that empathy and self-control developed in the early years reduce the likelihood of violent and criminal behavior later in life.

Interpersonal skills and the ability to learn, developed through close, stimulating contact with caregivers, are cost-effective investments that result in long-term benefits, including adult health, education, earnings, relationships, and social life. If these are denied in the early years, individuals can earn up to one-third less than their peers, as one study on the effects of early childhood intervention programs showed.

When they earn less, parents can provide less for their children, perpetuating the cycle of growing up in poverty for generations. At the societal level, the effects multiply, and missed opportunities are difficult and costly to compensate for.

In the end, what constitutes the magical formula for the best investment?

Good health, adequate nutrition, early learning opportunities, responsible parenting, safety, and protection.

Yes, a good portion of these cannot be bought with money, but enough money, combined with knowledge and love, already makes up a significant part of the magic.

As a non-mother, I am left to follow what science says about this magic and add economic arguments to the enchanting formula.

Economic reasons: spending money on a child’s health and happiness is a good idea

In economics, the idea of investing in people has been around since the beginning. This is because “acquired and useful abilities of all the inhabitants or members of the society as a source of wealth should be treated in the same way as fixed assets and physical capital”, as proposed by Adam Smith.

In contrast to physical capital, which sees profit as the main driver of social production, human capital means figuring out how much someone is worth by looking at their life and work skills, as well as their health, movement, experience, and so on.

From this point of view, children and their well-being can be seen through the lens of economics, which says that money should be spent on kids, especially when they are young. Scientists use evidence from biological and social sciences to show how important the first few years of life are for the economy.

Getting enough human capital at the start of your life is the only way to avoid getting stuck in poverty and productivity traps later on, according to James Heckman’s definition of human capital as “a combination of innate ability, education, and skills acquired through life experience”.

There is proof that kids who get a good education when they are young are better prepared to handle challenges later on in school. Because of this, there is less chance that these kids will develop mental problems and more chances that they will go to school and get better jobs.

The society is able to set aside more money for social benefits and unemployment allowances when the employment rate is high because more people are paying taxes. That’s good for society since it increases safety and lowers the cost of policing bad behavior.

An empirical case for investing in children: Bosnia and Herzegovina

UNICEF recently completed three reports on investing in early childhood development (ECD) in Bosnia and Herzegovina. These papers concentrate on three critical areas of early childhood development: health and nutrition, education, and social protection.

The country is dealing with an aging and decreasing population, which is providing substantial economic and social challenges. With fewer children and fewer resources, this country must focus on developing a trained and productive young workforce in order to improve economic and social conditions, concluded this research.

This investment pays significant social and economic returns, helping not only children and families, but society as a whole. It lays a solid foundation for development, improves the effectiveness of education and healthcare institutions, boosts economic production and growth, and promotes a society in which everyone has equal opportunity.

The investment cases in various sections of Bosnia and Herzegovina are based on thorough evaluations that compare the costs and benefits of services for children aged 0 to 6. They identified a set of Nurturing Care Framework-aligned interventions in each sector and then calculated the short-, medium-, and long-term costs and benefits of increasing these interventions.

According to the studies, investment in ECD is very cost-effective and results in significant economic returns. The research further emphasized that ignoring ECD has substantial economic consequences. This means that every monetary investment in ECD programs generates a strong, positive return on investment, notably by lowering preventable maternal and child health problems, improving educational performance, boosting lifetime wages, and reducing poverty and inequality. If Bosnia and Herzegovina does not make these ECD expenditures, it risks missing out on huge economic gains, potentially costing billions of dollars over the next thirty years.

These investment stories provide the most compelling evidence for prioritizing ECD in Bosnia and Herzegovina to date.

They are a significant tool for activists and decision-makers in the country concerned with children, assisting in the implementation of evidence-based, long-term social expenditures and, eventually, producing improved results for early children. To campaign for higher investments in children, advocates for children’s rights should use both economic and child-centric rhetoric.

They should also emphasize the critical role that early childhood development plays in economic and social development, as failing to invest in young children can undermine other initiatives, given that a well-educated, healthy, and productive workforce is essential for economic development, especially in light of demographic challenges.

Research about investing in young people still requires more evidence

The research I conducted in my dissertation several years ago emphasizes that investing in children’s well-being is a long-term investment in the next generation, not merely a short-term expense.

The evidence collected supported the hypothesis that it is critical to investigate the relationship between economic well-being and children’s welfare, as well as to comprehend the mechanisms for intergenerational investments in human capital.

This dissertation also made suggestions for further research on the economics of investing in children. The methods and data employed in my work provide numerous avenues for further research.

The practical recommendations include pressing for more expenditures in early human capital development across generations. This includes combating multifaceted poverty through social safety nets and increasing healthcare services to prevent child mortality. While further research is needed to determine the causal linkages between human capital investments and child well-being indicators, this analysis reveals a positive relationship between higher employment rates and less negative consequences for teenagers.

Researchers will need data on family material well-being, surveys on well-being among different age groups, family dynamics, age-specific participation in decision-making, and assessments of child and youth safety, protection, and dangerous behaviors to undertake such studies. Gathering, analyzing, and reporting this data involves enormous resources, particularly if a worldwide database covering numerous countries throughout time is desired.

How to change the public perception about early investments in human potential

Child well-being in society can be looked at through the lens of children’s rights, but it can also be seen as an investment that lasts for generations. This is shown by public investments that aim to improve the child’s status in society, such as funding the education, health care, and social protection systems for children.

People can also learn more about how important the first few years of life are and how important it is to make material and non-material investments for child-well-being. It is the job of the professional media to build and promote a stimulating environment for every child’s growth and well-being.

Based on ideas about how important the first few years of life are for the economy, this paper suggests that the way the public perceives children could be changed so that investments made now will pay off for future generations.

The people who create media contents help shape how people think about ideas, events, situations, or people by giving them attributes, either directly or indirectly, on purpose or unintentionally. Over time, a learned association is formed when ideas that haven’t been clearly defined as good or bad, helpful or kind are repeatedly and consistently described in detail.

People who read, watch, or listen to the media often accept these ready-made versions because they aren’t interested or able to question them. They accept the traits and characteristics of ideas, events, situations, or people that they are formed by the media.

On the other hand, economics shows that spending money on health care, education, and making people’s lives better in general increases society’s ability to make new things valuable.

People generally agree that “human capital” refers to the knowledge, skills, and experience that people have, either individually or as a group, that have economic worth. The word “capital” refers to money and other production assets that are used to make more money. The development of “human capital” is a key factor in economic growth and development. Evidence exists that Investing in the development of human capital has a better rate of return if it happens in the early years of life.

Changing how people think about children is everyone’s job

Media makers play a big part in changing how people see kids from things that are just there to look nice or have fun seeing them as important members of society. The way they were raised and the way things are now affect the future for everyone. If you write news stories, reports, movies, or participate in social media conversations, you need to take responsibility for how childhood is shown to the public. Putting money into kids’ health and schooling should be seen as an investment, not an expense, because it pays off in the long run. Real change can only happen if people speak out for better conditions for children and if the media and leaders change the way they talk to make children’s well-being the most important social investment.

Three Important Tips for Content Creators

Focus on how children are represented: Content creators, journalists and editors can change how children and youth are shown in the media. They should focus on spreading news about the health and safety of children with the same vigor that they do about infrastructure spending. Unity shouldn’t come from doing shady projects. Instead, it should come from being honest about what is being done to help kids.

Give Correct Information: Professionals and experts have a big impact on how the media tells stories about kids. By giving the media accurate information, they can speak up for children’s best interests and stress that any effort to help them is a worthwhile investment.

Advocate for Children’s Rights: Parents should not only help their kids grow, but they should also make sure that society does what it needs to do for kids. This means holding elected officials responsible and asking that children’s rights be protected. Laws like the Convention on the Rights of the Child make it clear that people care about this issue.

Justification for Investing in Child Well-Being: For a bright future, long-term investments in children’s well-being are necessary. The media and the people who make media material are both very important in promoting this cause. They can make things better by speaking up for the “best interests of the child” and starting conversations about these issues. Also, investments in money and budgets that are directly meant to improve a child’s well-being give better returns, which is backed up by both moral and legal reasons.

The people who make media, experts, parents, and society as a whole need to change how children are seen and respected in public media. We can make sure that future generations have a better life by spending on the health and happiness of children. This change in thinking is good for the child and helps the economy and society grow. We can make a safe place for every child to grow and learn if we all work together.

Ripple Effect of Timely Investments in Human Potential

The idea here is that improved development environments for children provide parents more time, energy, and resources to contribute to society. Despite its complexity and varied nature, human capital is frequently simplified in the literature by utilizing metrics that approximate its value, such as years of education (representing educational status) or mortality rates (as an indicator of health).

Few studies have attempted to quantify the investment in human potential, particularly in its early stages of development. An intriguing approach in the literature is assessing markers of children’s well-being, which investigates the issue from a legal and sociological standpoint rather than just an economic one. Human capital research is of great interest to social scientists, international development practitioners, and policymakers.

Understanding its origin, conceptualizing its meaning, and quantifying it can help us comprehend the factors that influence economic growth and long-term development in countries. Economists continue to investigate the interaction of economic forces of production, evaluating the quantitative cost and contribution of human capital to economic outcomes, as well as the intergenerational return on this sort of investment.

The return on investment in children includes economic and social ramifications, such as economic outcomes (e.g., GDP), reduced intergenerational poverty transmission, or lower overall spending on healthcare, education, and the social safety system. Literature demonstrates that investing in children, especially in their early years, reduces irreparable losses in future economic results, highlighting favorable benefits on individuals and long-term cumulative effects on society and the economy. The return on investment in children includes economic and social ramifications, such as economic outcomes (e.g., GDP), reduced intergenerational poverty transmission, or lower overall spending on healthcare, education, and the social safety system.

Dr. Claudia Goldin was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2023 for her pioneering work on the role of women in the workplace. Her research has shed light on the factors that contribute to gender differences in employment and earnings. Goldin’s research digs at why and how women frequently experience obstacles in the labor market and in earning a living. Notably, she is just the third woman to earn this distinguished award, emphasizing the importance of her contributions to the profession.

In a recent research paper by Dr. Goldin, along with Sari Pekkala Kerr and Claudia Olivetti, the authors emphasize an essential issue: women often earn less than males, and this inequality is even more obvious when comparing moms to fathers. The research reveals that a considerable percentage of this income disparity widens once mothers reduce their working hours following the birth of their children.

But what happens as the youngsters grow up? To answer this question, the researchers looked at three key factors: the “motherhood penalty,” which refers to the earnings gap between mothers and childless women; the “price of being female,” which represents the gender-based wage gap between women and men; and the “fatherhood premium,” which describes the income advantage fathers have over childless men. When you combine these three elements, you get what they call the “parental gender gap,” which assesses the difference in income between mothers and fathers.

The authors used data from the US National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79), which tracked respondents from their twenties to their fifties, to estimate these wage discrepancies for two educational groups: college graduates and high school graduates who didn’t attend college.

As children grow up and women gradually increase their working hours, the negative impact of the parenting penalty is dramatically lessened, particularly among the less-educated group. However, fathers somehow manage to boost their relative financial advantages, especially among college graduates. In the end, the income discrepancy between mothers and fathers, known as the parental gender gap, remains large for both schooling levels.

In conclusion, timely investments in human potential, especially in children, yield substantial economic and social returns, benefiting not only children but society as a whole. The media, experts, parents, and society collectively play a vital role in changing the narrative and promoting the well-being of future generations.

To address these issues, there are already advocacy initiatives, like Moms First in the US or Mamforce in Croatia.